GMOs, tobacco, bisphenol A, asbestos: Stéphane Foucart, science correspondent at “Le Monde”, dissects in “The Lie Factory” [“La Fabrique du mensonge’’] the methods used by large companies to manipulate science to their advantage.

Le Monde, 21 March 2013. (English translation from French original by New Europe Translations)

In 1953, the headlines of all the big American newspapers linked for the first time lung cancer and smoking. These revelations had a significantly adverse effect on the tobacco industry, who called an emergency meeting in New York. John Hill, who was responsible for the counter-attack by cigarette manufacturers, laid the foundations for a terribly malicious communication strategy by financing serious studies that manufactured scientific doubt and contributed to the public acceptance of cigarettes. Stéphane Foucart, journalist at “Le Monde’’, explores the fingerprints of big firms on scientific research. In “La Fabrique du mensonge’’ he uses a fine tooth comb to go through the industries that follow the path of the tobacco industry and have a negative impact on our life expectancy. This compilation of investigations tells how manufacturers get leading researchers to take the bait and succeed in spreading their concepts through the media and in discussions. The book lifts the veil on the bisphenol A health scandal, the lobbying of French manufacturers in the asbestos affair, and the financing of think tanks by companies whose interests are affected by climate issues. We learn how the industries responsible for ecological disasters and the death of millions of people muddle the discussion to gain time and maximise their profits. Some revelations about this capture of science are chilling. Jean-Roch de Logiviere

[Excerpts from Stéphane Foucart’s book, The Lie Factory]

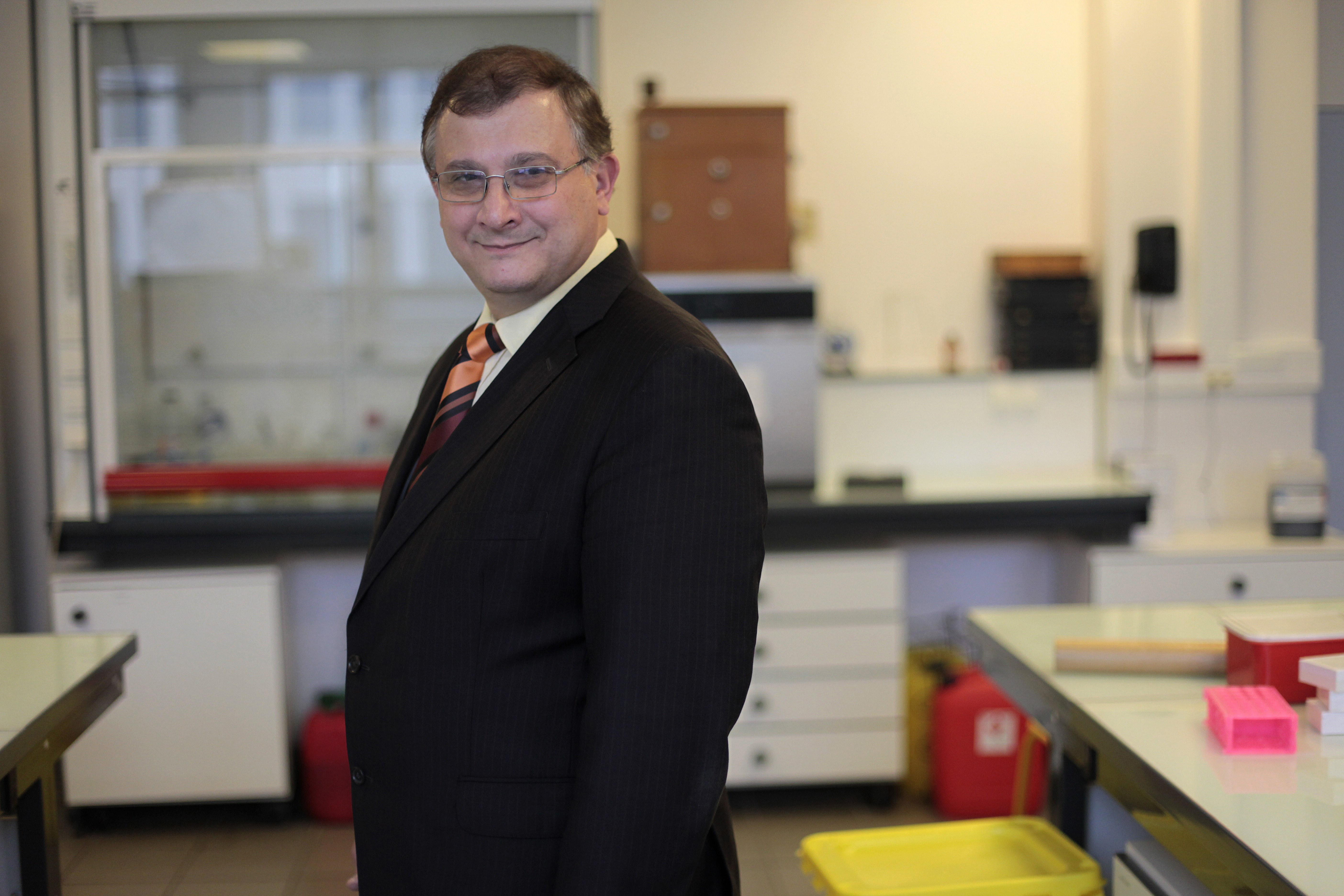

On 27th September 2012, ten days after the publication of the work conducted by Gilles-Eric Séralini [author of a study on the toxicity of a GMO and its associated herbicide], Le Monde received by email a curious proposal for an article on the French biologist’s work. It originated from two ageing researchers, the toxicologist Bruce Chassy, Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois, and the biologist Henry Miller, the Hoover Institute (Stanford University). Curiously, the article is addressed directly by the two American scientists to the former head of the “Debates” pages of the daily newspaper, while the name of the latter no longer appears as such in the newspaper’s masthead.

In general, unsolicited articles reach the default email address, except if their author was, at one time or another, in connection with an editing journalist. Here, no such thing. Bruce Chassy and Henry Miller do not know anyone in the editorial staff of Le Monde. How the heck did they know who to send their text to? All this is almost certainly the sign of an intervention by a public relations firm: the name of that journalist had obviously been found in an obsolete “press file”. These files are used by communication companies to target their press releases to this journalist or another, depending on their position and/or interests. Another reason to be surprised is that their article is written in perfect French, whereas their email is in English. Therefore, who took the trouble and time to produce such an excellent translation of their original text that we imagine had been written in English?

Another question is why the text is so aggressive towards the French biologist. To dispute the methodology of a study, its interpretation of the data, etc. is one thing. To immediately call it “fraud” and “scam” is defamation pure and simple. The title of the article suggested by the two American researchers was the following: “Scientists smell the scam in a fraudulent genetic engineering study’’. The remainder of the text is altogether completely defamatory and very sketchy: “The microbiologist Gilles-Eric Séralini, and several colleagues have released the results of a long-term study in which rats were fed genetically modified maize (called ‘GMO’) resistant to insects and/or to the herbicide glyphosate”, while the focus of the study has nothing to do with an insect-resistant maize. That raises serious doubts whether these two scientists had even read the work they intended to take apart.

“The experiments presented last week show that [Gilles-Eric Séralini] has crossed the line between simply conducting and publicizing imperfect experiments and committing serious scientific errors with attempted fraud,” they added. “It is also important to note that the publication of this article constitutes an abject and unbelievable failure of the editorial competence of the peer-reviewed journal Food and Chemical Toxicology”, said the two researchers, who were full of resentment.

Welcoming the fact that some journalists had not included the French researcher’s findings in their reports, they said: “Maybe we have reached a point (…) when the media finally realise that they have been manipulated for years by experts and professional scammers”.

The use of aggressive language, the targeting of the journalist whom the article was sent to, the text written in impeccable French… All this suggests a coordinated attack rather than a spontaneous kneejerk reaction by two researchers with a love of scientific rigour.

Who are these two scientists? Their CVs are prestigious. One of them, at least, is not totally unknown to us. We have already come across Henry Miller: the tobacco documents (the secret documents of the tobacco industry, declassified in 1998 by a court ruling) show that he was engaged in activities with the Advancement of Sound Science Coalition (TASSC), the think tank created by Philip Morris to attack “bad science”, that is, science that can lead to regulatory restrictions.

(…) In 1992, since the publication of the report of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) showing the harmful effects of passive smoking, Philip Morris had considered the creation of a group dedicated to become the vehicle – to the media, decision makers and also of part of the scientific community – of this systematic opposition between “bad science” (“junk science”) and “sound science”. In order not to attract suspicion, the creation and management of this think tank were entrusted to a public relations company, APCO Associates. Thus was born, in February 1993, the Advancement of Sound Science Coalition.

At the beginning of 1993, a memo from Philip Morris introduced the project: “our primary objective is to discredit the EPA report and to get them to adopt the same standards of risk assessment for all products”.

The memo described the plan of action of the first weeks of activity, fixed a budget of nearly $350,000 for the first six months of existence of the notorious think tank and considered it essential to gather various manufacturers to form a coalition of interests. The first efforts were primarily to recruit scientists into the TASSC, to identify journalists likely to go with what manufacturers promote, to send letters to newspapers…

“Without an effort to build reasonable doubt about passive smoking – especially amongst consumers, then virtually any other effort (…) will have a significantly reduced efficiency,” explained a senior member of staff of the firm from Richmond[?] in a February 1993 memo. The same internal mail added, in bold: “The EPA’s credibility can be defeated, but not solely on the basis of passive smoking.” “This must be part of a vast mosaic, which will bring together all the EPA’s enemies at the same time,” said the document. To maximize the effectiveness of the movement, we must launch a front against all scientific disciplines used at the EPA and the industry must be united against the environmental sciences.

Another advantage sought by Philip Morris was to expand the number of corporate partners in the TASSC. Therefore, if embarrassing questions from journalists were to arise about the sponsors of the Organization, APCO associates would be able to quote a large number of companies without an apparent and direct relationship with each other. Above all, the scientists recruited into the think tank could swear “hand on heart” that they received no subsidies from the tobacco industry, since their invoices were paid by APCO Associates. Nevertheless, the tobacco documents showed that the public relations firm took no initiative without referring first to the cigarette manufacturer.

Spokesmen for Big Tobacco wanted to make Henry Miller the chair of a European think tank, similar to the American TASSC, which would have been responsible for promoting “good science” in the media. It is unclear whether this project took off or in what form – the tobacco documents do not mention it. However, Henry Miller did indeed propose articles to the European media to combat “bad science”.

A message from the editorial staff of Le Monde was addressed to him and to his colleague, Bruce Chassy, asking them if their article had been drafted and suggested to the newspaper on behalf of a company or an institution and, if so, which one. This message did not receive a reply or even an acknowledgement from the stakeholders [Miller and Chassy].*(…)

Henry Miller is the author of some twenty-six articles published in the British newspaper The Guardian, or on its website, between 2008 and 2011, all celebrating genetic engineering, agrochemicals, deregulation, etc. He also has a blog on Forbes magazine’s website, and some of his posts are published in the daily press across the United States. Between 2006 and 2007, he managed to get no less than ten articles in the New York Times, the most prestigious American newspaper.

We do not know the details of this mechanism. We do not know what is behind it. But the tobacco documents can enlighten us on how things were going, a few years ago. Henry Miller appears repeatedly in the internal documents of the tobacco giants. In an internal Philip Morris memo dated January 1996, a senior member of staff informed his hierarchy: “I spoke to Henry Miller, from the Hoover Institute, about another article in the press. He was interested but wanted to learn more. If he agrees, we will send him to the main newspapers in the districts of committee members.”

The document does not specify the nature of the parliamentary committee in question. Another internal memo from [tobacco company] RJ Reynolds, dated June 1995, explained that two company spokesmen “worked with Dr. Henry Miller to circulate his article”. “So far, it has been published in the San Diego Union, the San Jose Mercury News and the Washington Times,” adds the document.

Working with [the public relations company] WKA, they sent the article to thirty daily newspapers that they had selected with the original paper by Dr. Miller, and they phoned the heads of editorial staffs in order to encourage them to publish it. Dr. Miller is also eager to take part in hearings if necessary.” The document does not mention which “hearings”, but the offer made by Henry Miller suggests a very close link with the company.

Henry Miller appears even as the author of a “Work Plan to promote sound science for health, environmental and biotechnology policies”, dated September 1998, proposed to the cigarette manufacturer Brown & Williamson. The project aimed to “offer a solid and multifaceted approach (…) to expand and strengthen efforts to influence opinion leaders, politicians and, above all, ordinary citizens,” explained Henry Miller. (…) The use of media articles is one of the central elements put forward by the scientist, who asks for 5,000 to 30,000 dollars depending on the service (translation or not of texts in Spanish for the Latin American press, etc.), the most expensive including “writing a book about the environmental policy of the United States”, as well as the use of the Internet, fax, etc. to reach a wider audience. The tobacco documents do not allow us to know if the programme proposed by Henry Miller ultimately received endorsement and approval by the multinational’s bosses.

(…) However, it has to be said that the aggressiveness of his opponents and the likely lack of sincerity of some of them, do not necessarily prove, from a scientific point of view, that Gilles-Eric Séralini is right.

*Henry Miller’s response came after the final proof for the book. Mr. Miller confirms that the article given to “Le Monde” had been written by the authors’ “only initiative”. “I believe that Mr. Chassy got the name [of the journalist from Le Monde’s editorial staff] from someone at the United States’ Embassy in Paris,” he adds. Mr. Chassy gave no response to the demands of the author. Without disputing the authenticity of the internal documents from the tobacco industry that mention him, Mr. Miller also said that he had “never received money or compensation of any kind by a tobacco company”.