In September 2012 the journal Food and Chemical Toxicology (FCT) published the research of a team led by the French biologist Professor Gilles-Eric Séralini, which found liver and kidney toxicity and hormonal disturbances in rats fed Monsanto’s GM maize NK603 and very small doses of the Roundup herbicide it is grown with, over a long-term period. An additional observation was a trend of increased tumours in most treatment groups.

In November 2013 the study was retracted by the journal’s editor, A. Wallace Hayes, after the appointment of a former Monsanto scientist, Richard E. Goodman, to the editorial board and a non-transparent review process by nameless people that took several months.

Report: Claire Robinson Source: gmwatch.org

Did Monsanto pressure the journal Food and Chemical Toxicology (FCT) to retract the study? French journalist Stéphane Foucart addresses this question in an article for Le Monde.

The article shows the total subordination of Goodman to Monsanto. It also reveals how Hayes played a double role in the retraction of the study, acting behind the scenes to encourage Monsanto scientists to join the reviewing panel that would feed their views into the decision to retract.

Influence of chemical companies on academics

Foucart examined emails disclosed as a result of a freedom of information request submitted by the food transparency organisation US Right to Know (USRTK). Foucart writes that the emails “reveal the influence of the chemical companies on some academics”.

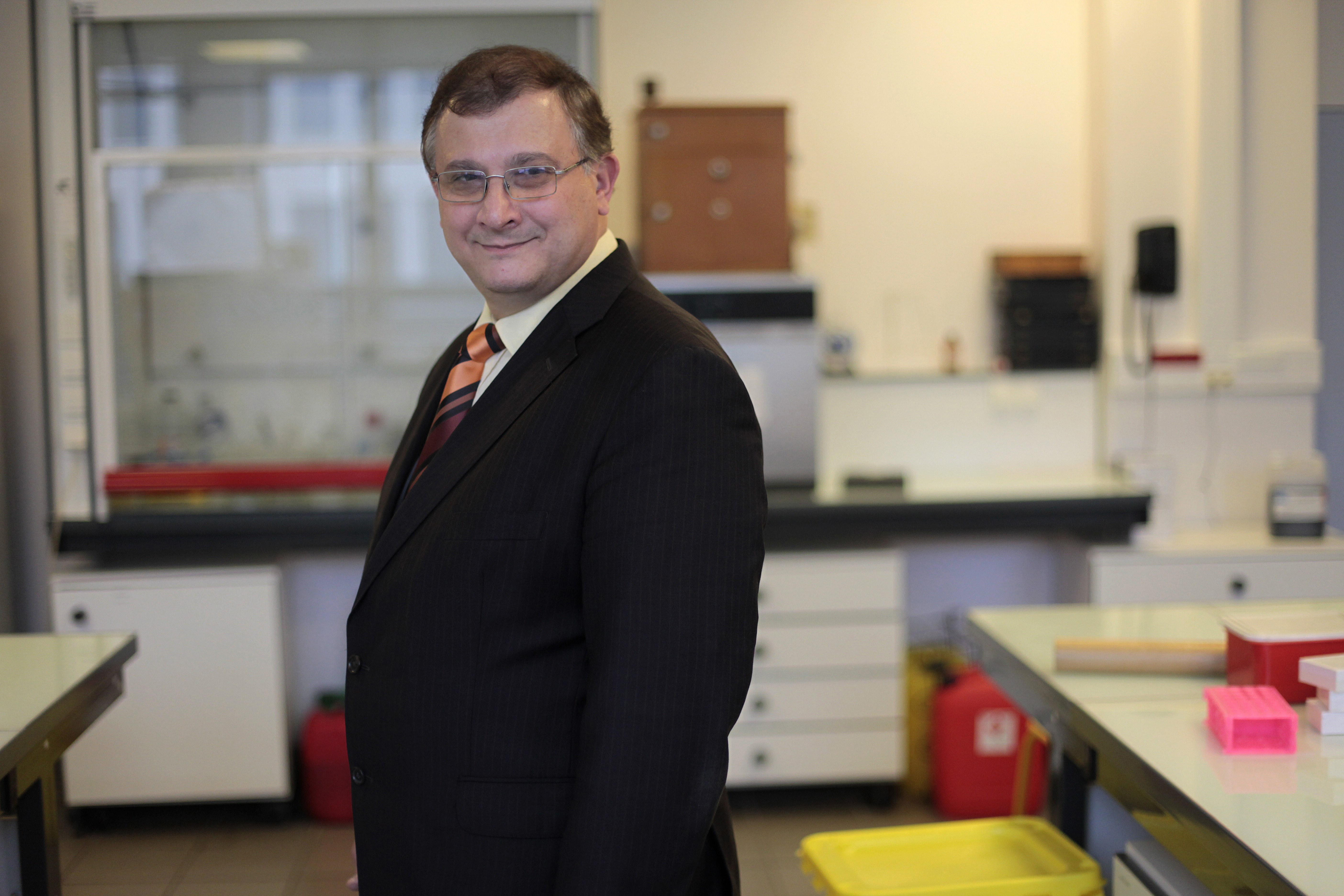

Foucart points out that scientific papers are normally retracted only due to fraud, plagiarism, or honest error. Séralini’s study did not fall into any of these categories and was the first to be retracted on grounds of “inconclusiveness”. Supporters of Séralini challenged a newcomer to the editorial board of FCT, in charge of biotechnology. Richard E. Goodman is a Professor at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln (USA) and specialist food allergens. He is also a former employee of Monsanto, which he left in 2004.

FCT biotechnology editor had “remarkable closeness” to Monsanto

Foucart writes that emails obtained by USRTK show “a remarkable closeness” between Goodman and his old employer. In reality, however, as Foucart points out, the relationship between Goodman and Monsanto is not so old. Goodman himself wrote in a message of 2012 that “50% of [his] salary” actually comes from a project funded by Monsanto, Bayer, BASF, Dow, DuPont and Syngenta, and consists of establishing a database of food allergens.

This fact, Foucart notes, creates “links, or even a subordinate relationship” between Goodman and Monsanto. Foucart goes on to explain how that subordinate relationship manifested in an incident that happened in May 2012, before the publication of the Séralini paper in September of that year:

“After the publication of a newspaper article in which he is quoted, Goodman, not yet an editor at FCT, is sharply brought to order by a Monsanto employee. The latter tells the professor that his opinion seems to have been interpreted by the journalist as ‘suggesting that we do not know enough about biotechnologies to say that they are safe’. In return, Goodman wrote a collective message to all his correspondents in the six biotechnology companies that fund his work. ‘I apologize to you and your companies,’ he wrote, adding that he was misunderstood by the journalist.”

Industry financing of science imposes control over researcher

Foucart comments that the financing of scientific work by industry means for university researchers a commitment that goes far beyond the simple production of knowledge: “It imposes a form of control over the public discourse of the researcher.” In August 2012, Goodman took the lead and warned his sponsors that he would be interviewed by National Public Radio on the safety of GMOs. “Would you participate in a media training session before the interview?”, asked one of his correspondents. It is not known whether Goodman accepted this proposal, as he did not respond to Le Monde’s inquiries.

A month later, in September 2012, the study by Gilles-Eric Séralini was published. Goodman was not at the time a member of the editorial board of FCT. On 19 September, Foucart writes, Goodman informed his Monsanto correspondent about the publication of the Séralini’s article and that he “would appreciate” it if the firm could provide him with criticisms. “We’re reviewing the paper,” the Monsanto correspondent replies. “I will send you the arguments that we have developed.” A few days later, Foucart writes, Goodman was named “associate editor” of FCT, on the decision of the toxicologist Wallace Hayes, then editor of the journal.

This appointment was not publicly announced until February 2013. Foucart notes that the addition of Goodman on the editorial board of the magazine was actually a direct and immediate consequence of the publication of Seralini. On November 2, 2012, when the “Séralini affair” was in full flow, Hayes announced in an email to Monsanto employees that Goodman would from now on be in charge of biotechnology at the journal. Hayes added: “My request, as editor, and from Professor Goodman, is that those of you who are highly critical of the recent paper by Séralini and his co-authors volunteer as potential reviewers.”

Foucart comments that Hayes was formally inviting Monsanto toxicologists to appraise for acceptance or rejection studies on GMOs that are submitted to the journal for review. The documents consulted by Le Monde did not say if Hayes – who has not responded to Le Monde’s inquiries – limited this request to Monsanto scientists.

This confirms that we at GMWatch were right to question the arrival of Goodman on the editorial board. It also shows that we were right to criticise the non-transparency of the second round of review (the first review being the one that led to the study being published). Some observers told us they thought it was acceptable that the reviewers remained anonymous, since peer-review is generally an anonymous process. But this particular ‘review’ – of a paper that had already passed peer-review, had been published for a year, and had nothing wrong with it beyond the fact that, in common with countless other scientific papers, it was “inconclusive” on some endpoints – was a highly irregular process of dubious legitimacy from the start. Therefore we believe that the identity and interests of the reviewers should have been published.

Another GMO-critical study rejected by FCT

Foucart notes that there is no way of knowing for sure if all this had an impact on articles accepted by the journal. But in 2013, according to information received by him, FCT rejected the first academic study of chronic toxicity of a Monsanto GM maize – MON810 – in Daphnia magna, a type of waterflea. The study suggested harmful effects on this small freshwater crustacean, which is used as a model organism by ecotoxicologists.

It was Goodman who informed the authors of the rejection, highlighting the negative reports of the peer reviewers. The study was eventually published in 2015 in another journal. Unlike the Séralini study, it was not challenged (probably because, unlike a rat feeding study, such a study would not be deemed by regulators to be relevant to humans).

Goodman asks Monsanto for scientific arguments to counter critics

In some cases, Foucart reports, Goodman seems to defer to the judgement of Monsanto’s toxicologists which he has to evaluate an article containing aspects that are beyond his knowledge. “I’m looking at an ‘anti’ [presumably ‘anti-GMOs or pesticides’] paper,” he wrote in October 2014 to one of his Monsanto correspondents. “They cite a Sri Lankan study of 2014 on a possible link between glyphosate exposure and kidney disease, as well as a mechanism [to explain this toxicity].” Goodman added: “I’m not enough of a chemist or toxicologist to understand the strengths and the weaknesses of their logic: can you give me some solid scientific arguments about whether it is, or is not, plausible.”

Glyphosate, the active ingredient of Roundup herbicide, is a key product of Monsanto, as it is sold with the company’s GM glyphosate-tolerant crops.

According to Foucart, nothing in the documents consulted by Le Monde supports the idea that Goodman played a role in the retraction of the Séralini study – that decision was taken by Hayes. In January 2015, Goodman resigned his position at the journal, due to time constraints.

Hayes’s conflicts of interest

However, Hayes clearly did play a key role in the retraction. And he has plenty of conflicts of interest that might have influenced his decision.

Hayes has had a long career as an industry toxicologist. He is senior science advisor at Spherix Consulting, “a global team of experienced advisors who provide their clients in the food, dietary supplement, consumer product, and pharmaceutical industries with scientific solutions that result in regulatory success.”

Hayes’s previous appointments include:

- Vice President and Corporate Toxicologist for food giant RJR Nabisco, with responsibility for all regulatory and toxicology issues related to the safety of ingredients and food contact substances for food and drink products worldwide.

- Corporate Vice-President of Product Integrity at the Gillette Company, with responsibility for “the safety evaluation and regulatory compliance of a variety of consumer products, plant safety, environmental stewardship, and quality control. While at Gillette, Dr Hayes was responsible for managing regulatory and toxicology issues worldwide. All contact substances used in Gillette products (including personal care products) were cleared within his division.

Industry interests prioritised over science

Hayes’s interests and Goodman’s current Monsanto connections should have precluded them from having any authority over the fate of the Séralini study and other studies submitted to FCT. In addition, the names of the reviewers who fed their views into Hayes’s decision to retract the study should have been declared and made public and any conflicts of interest should have led to exclusion from the panel.

Instead we have a situation in which a lack of transparency at the journal FCT allowed industry interests to take precedence over scientific considerations. In the process, the reputation of honest scientists has been unjustly maligned and public trust in science has been damaged, perhaps irretrievably.