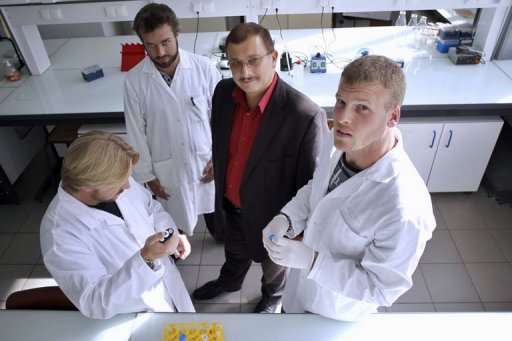

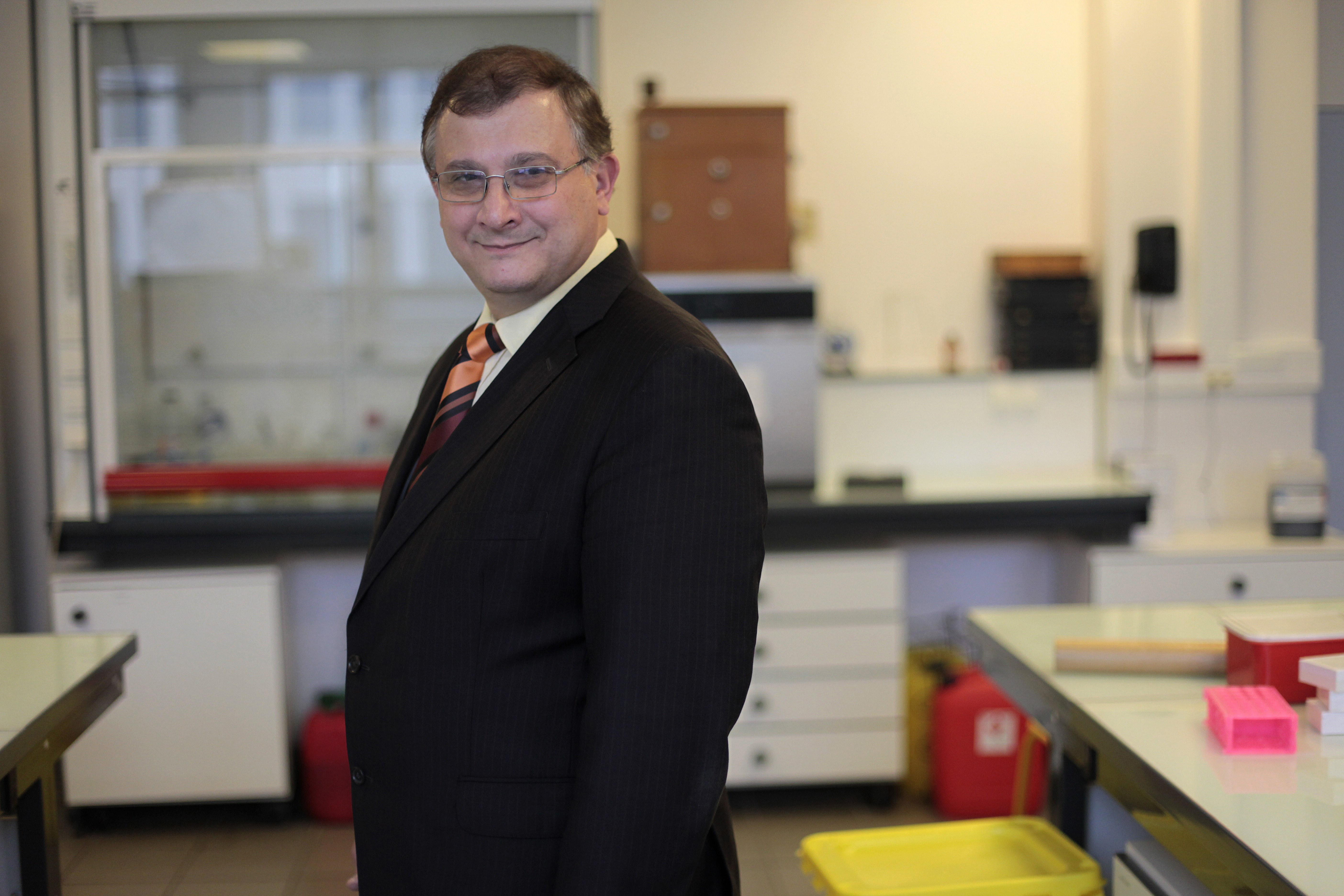

Taking on a biotech giant is tough. James Fitzgerald talks to one researcher who came out fighting – Professor Gilles-Eric Seralini

The release of the “Monsanto Papers” late last year made headlines around the world and raised further doubts about the efficacy and strategies of the biotech giant. What is less known is the private battle by a French scientist to institute robust testing protocols for genetically modified organisms and pesticides.

Source: chief-exec.com

Here, Professor Gilles-Éric Séralini details his efforts to quantify the risks of GM maize, but not before providing a crash course in evolutionary plant biology.

“From a biological perspective, fruit did not evolve so as to feed birds, insects, molluscs or humans. Fruit existed millions of years before us,” he tells Chief-Exec.com.

So what spurred the evolution of fruits?

“The fruit is a placenta, an egg: a storehouse for the plant embryo. It only appeared with flowering sexed plants over 200 million years ago. It provides food to its own seeds or to the core when it germinates. So it gives the embryonic plant stamina. It is a ‘pantry’ in a difficult environment, where soil and organic matter may be rare.”

It seems that eating is not so much consumption as transformation – and recirculation, as no energy is actually destroyed.

“In a vegetable, herb or the flesh of a fish, we can eat the carbon which passed through the blood of the first men, the pyramid builders or our grandmothers. If the carbon is trapped with a pollutant, such as plastic, it will be more stable, and will remain in our bodies.”

This leads us into questions over authenticity versus mimicry – what constitutes natural and what is synthetic. Even vintners cannot escape the modern quandary over micro-organisms in vials or meadow flower aromas.

“By using pesticides such as Roundup to weed their vines, they sterilise their soil, killing microbes, fungi and yeasts. But these micro-organisms favour the formation of new flavours: their disappearance causes a reduction in the aromatic quality of the grape harvest,” says Prof Séralini.

“A living, quality ‘terroir’ is also important in obtaining good dairy products. Today there is such a loss of the biodiversity of natural organisms sensitive to Roundup that the use of vials of micro-organisms (reproduced in the laboratory) has become essential in the production of cheese.”

The confrontations between pro- and anti-GMO groups often revolve around the philosophical premises of “Nature is poorly formed and needs human modification” or “Nature is perfectly created and sacred”.

“For me, that’s not the problem. It’s how GMOs are used and the planned poisoning of life that follows on from it: we transform plants into pesticide factories; we use consumers as guinea pigs and the environment as a laboratory, while the genetic modifiers claim ownership of this life through patents (another aspect peculiar to GMOs).”

But if genetic modification is used to produce medicines, then it presumably occupies some hallowed ground also?

“GMOs are important and even necessary research tools in the laboratory. They allow us to understand the role and function of genes and to produce pharmaceuticals in simpler ways than by chemistry. In that regard I am a ‘GMO lover’.”

Production of growth hormones is one beneficial use of GMOs. Modified bacteria are reproduced in an incubator to make them produce this hormone. “Molecular biological processes have enabled the identification and isolation of human genes and their introduction into bacteria which are used to produce these hormones – always in incubators.”

“Pesticide plants” account for more than 99 per cent of GMOs spread deliberately into the environment for agricultural use. This is not beneficial according to Prof. Séralini, it is quite the opposite. What exactly are pesticide plants?

“For about 20 years only two genetic-engineering characteristics – tolerance to herbicides and insecticide production – have been used for the four main transgenic plants intended for animal feed, and afterwards for humans. This accounts for a significant percentage of global agriculture. It is this usage that makes debate imperative.”

These four crops are soya, maize, cotton and rapeseed.

Prof Séralini says that over two-thirds of commercial GMO plants – for all species – are modified to tolerate one or more herbicides. In an effort to simplify intensive and industrial agricultural practices, usage of glyphosate, a declared active ingredient of Roundup and one of the most common weed killers, is being expanded. “Roundup kills everything in its path, not glyphosate” he says.

Researchers have found that that glyphosate-based herbicides include other additives which not only have their own toxicity, but also enhance glyphosate toxicity[1]. “Heavy doses are sprayed on fields of transgenic soya, maize, cotton and canola [rapeseed] in order to desiccate all other plants.”

Prof Séralini first started studying its toxicity in 2005 at his laboratory at the University of Caen. He says plants are made tolerant to the herbicide through the transfer of DNA from bacteria and viruses that can live in environments contaminated by the pesticide. This process confers on them these new traits. “The farmer no longer needs to choose a weed killer according to the weeds that disturb his vast crops. He has just to spray Roundup.”

Prof Séralini started out as a research scientist studying the possible link between the pollutants in food and hormone-dependent cancers. This, he says, alerted him to the chemical disruption which can, over many years, lead to so-called “lifestyle diseases”, such as cancers and decreased fertility. His studies took in the effects of pesticides and GMOs on health.

He went on to teach molecular biology and genetic engineering at the University of Caen. “Over 10 years I researched possible causes of breast cancer. This research was conclusive in pointing to the importance of carcinogens originating from environmental pollution, and which accumulate in the breast and elsewhere,” he says.

As a consultant expert on “national and international assignments” he observed the safety assessment studies for GMOs and the process by which they are submitted by multi-national corporations to governments and the European Food Safety Authority. He claims problems arose because of a laxity in scientific rigour and the strict confidentiality attached to the results.

“The manufacturers did more or less what they wanted, with minimal effort, and were barely troubled by the lack of requirements from the undemanding agencies or committees.”

These apparent risks taken over public health motivated Prof Séralini to set up a study that was “difficult but rigorous at the scientific level”. His “in vivo” – which means with live animals – lasted from 2007 to 2012 at a cost of €3.2m.

As a co-founder of CRIIGEN (the Committee for Independent Research and Information on Genetic Engineering), Prof Séralini brings an interdisciplinary approach to considering the benefits and risks for human and animal health, and ecosystems, from genetic engineering and xenobiotics (artificial pollutants).

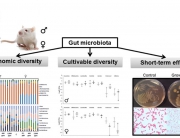

“We thought that by setting up a real-life situation – feeding GMOs to rats over their entire life – would we get closer to the reality of the effects,” says Prof Séralini . “If these rats withstood being fed these GMOs and the pesticides they produce throughout their life while remaining in good health, then we could perhaps assert that there was only a slight risk to human and animal health. We could then decide whether or not to move towards clinical testing, as is done for drugs.”

Public opinion intensified after media reports focused on Faucheurs Volontaires, a French activist movement which began to remove GM crops from fields. This coverage, says Prof Séralini, together with some scientific criticisms, prompted Monsanto to improve its next test.

The rats in Monsanto’s trial consumed a feed containing one of its GMOs, the Roundup-ready NK603. But, says Prof Séralini , there was a problem. The tests were stopped after 90 days. It only took into account the two measures of blood and urinary parameters; after five weeks and at the end of the 90-day feeding trial.

“Despite these two biases, in analysing the results, we realised that the first signs suggesting toxicity appeared in the analysis.”

A court ruling in Germany in 2005 required Monsanto to comply to a request by Prof Séralini to release its raw data. His group reported that in Monsanto’s study, the females developed pre-diabetes metabolic symptoms and the males renal insufficiencies. It was unclear if these were temporary complications.

Prof Séralini then conducted his own study on the same type of rats, but over a longer time period.

They used 200 animals – 100 females and 100 males housed in “ideal conditions”.

It should be noted that the issue of exposure durations is a controversial subject, with a counterview that cancer susceptibility increases with age in experimental animals.

“On several levels, the whole of our protocol exceeded that of the testing performed by manufacturers for the introduction of any of their products into the market. First by duration, taking over two years, our study lasted eight times longer than Monsanto’s testing on the same GMO [maize NK603]. Next, it exceeded both in total number and frequency of parameters studied…”

As early as one year, the results came as a shock. “Mortality in all the female groups that had consumed Roundup or GMOs was two to three times higher than in the control groups; and, above all, death occurred much earlier… We observed a similar difference in the three groups of males fed on GMOs,” says Prof Séralini.

The animals were also affected by severe kidney inflammations (1.3 to 2.3 times more). For both gender groups, biochemical data confirmed “highly significant chronic renal insufficiency”.

The photographs of female rats with large mammary tumours were picked up by sections of the media and circulated around the world.

Prof Séralini says the disruptive effects of Roundup are not proportional to the dose (as for all hormonal effects), but also linked to the “over-expression” of transgenes (artificial genes added to the modified plant) that “allow the GMOs to tolerate Roundup and its metabolic consequences”.

The study’s release in 2012 – in the journal Food and Chemical Toxicology (FCT) – triggered a strong emotional reaction from the public.

Prof Séralini says that the first wave of criticism came mainly from plant biologists, and not toxicologists. Responses to the issues raised were published in FCT in November 2012. But a second wave of “ad hominem and potentially libellous attacks” appeared in several other journals. He says that some of the authors may have had serious undisclosed conflicts of interest. The scientific remarks focused on the assumption that the “Sprague Dawley” rat strain was unsuitable, whereas it is a standard approach in toxicology.

In November 2013, in a highly unusual move, the original study was retracted by the Food and Chemical Toxicology journal. It was later republished by Environmental Sciences Europe, though arguably reputational damage had been sustained as the controversy flared.

The release of the Monsanto Papers (see our related article “Knock-out round for Roundup”), reveal internal documents that shed doubt on the credibility of some studies used in the European Union evaluation on glyphosate. They justify the concerns raised by Prof Séralini and his team of researchers over the last 10 years.

A tranche of documents was published by a court in California in March last year, following a claim by plaintiffs in a Roundup multidisciplinary litigation.

“The Monsanto Papers tell an alarming story of ghostwriting, scientific manipulation and the withholding of information,” says Michael Baum, a partner at Baum, Hedlund, Aristei & Goldman, the law firm behind one of the US class actions. Baum likens Monsanto’s tactics to those of the tobacco industry: “creating doubt, attacking people, doing ghostwriting”.

The debate and potential consequences for human health and ecosystems, rages on, with even regulators now caught in the line of fire. It seems nobody will be left untouched by the sinister or dynamic – depending on your point of view – forces we have unleashed.

Notes

[1] R. Mesnage, N. Defarge, J. Spiroux de Vendômois and G.E.Séralini. Potential toxic effects of glyphosate and its commercial formulations below regulatory limits. Food and Chemical Toxicology 84: 133-153, 2015.

This interview contains extracts from The Great Health Scam, by Gilles-Éric Séralini and Jérôme Douzelet; published by Natraj Publishers