Laboratory rats are frequently used for testing chemicals and genetically modified (GMO) foods, as the last step before commercialization in order to determine effects on mammalian health and predict risk in humans.

Such chemicals include pesticides (which often are endocrine disruptors or toxic to the nervous system), plasticizers, and food additives. Some are suspected of being carcinogenic, and others are gradually being banned after having poisoned people and the ecosystem.

Published in PLOS ONE (June 2015) – http://journals.plos.org

Source: CRIIGEN Press Release

However, health agencies consider that a high proportion of laboratory animals are predisposed to developing many diseases, based on industrial data archives known as “historical control data”. According to these data, 13–71% of the animals would spontaneously or naturally present mammary tumors and 26–93% pituitary tumors, and the kidney function of these animals would frequently be deficient. This prevents the attribution of observed toxic effects to the products tested, and requires the sacrifice of a large number of animals in an attempt to observe statistically significant results in carcinogenicity tests, for example. But often, doubt persists and the product remains on the market. Do these diseases originate from genetic or environmental factors?

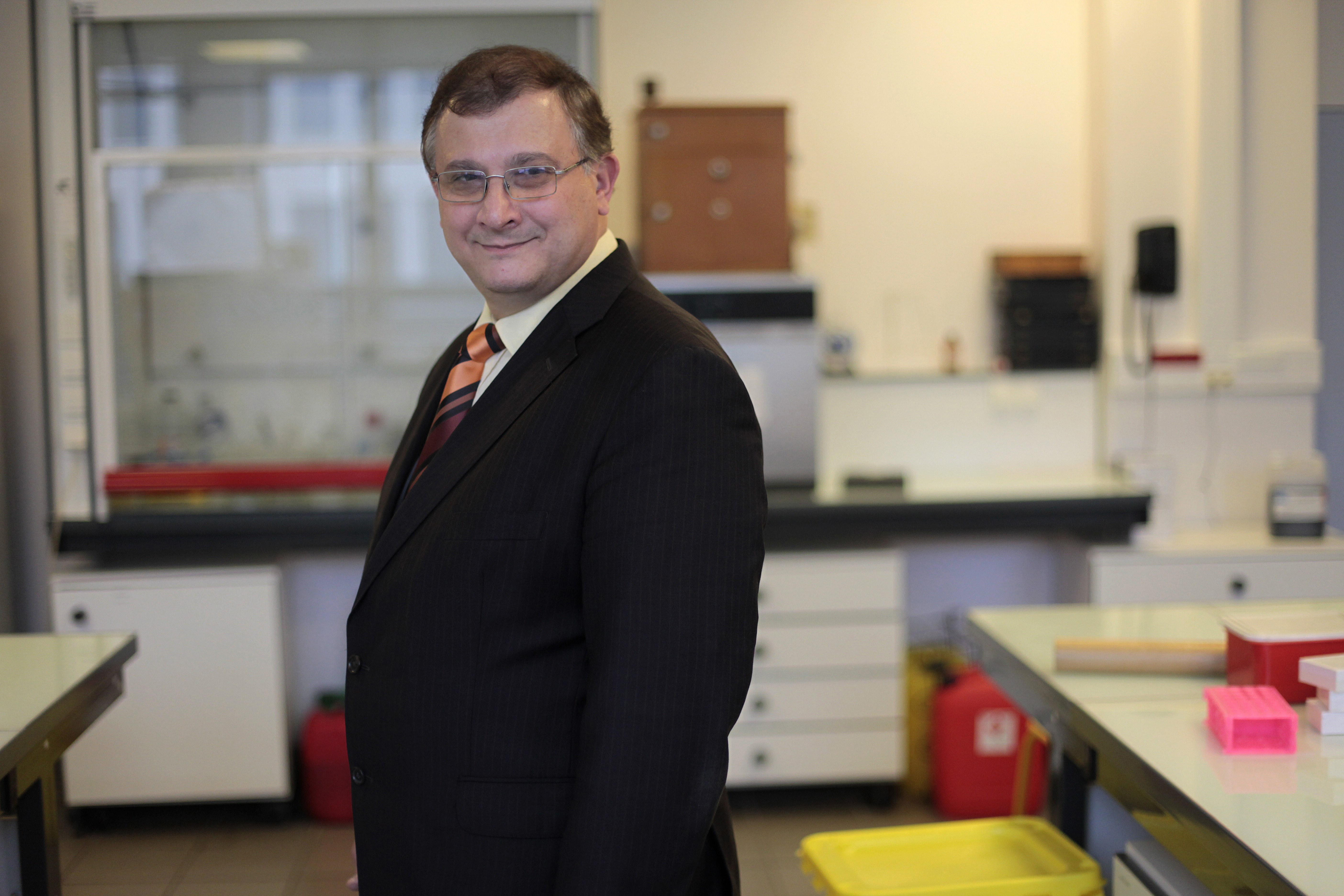

To investigate this question, the team of Professor Gilles-Eric Séralini of the University of Caen, supported by CRIIGEN, analyzed the dried feed of laboratory animals using standard methods and with the help of accredited laboratories. These animal feeds, sourced from five continents, are generally considered balanced and hygienic. The study was exceptionally wide-ranging; it investigated 13 samples of commonly used laboratory rat feeds for traces of 262 pesticides, 4 heavy metals, 17 dioxins and furans, 18 PCBs and 22 GMOs.

The results were overwhelming. All the feeds contained significant concentrations of several of these products, at levels likely to cause serious diseases and disrupt the hormonal and nervous system of the animals. This hides the effects of the products tested. For example, residues of the most widely used pesticide in the world, consisting of glyphosate and highly toxic adjuvants, such as Roundup, were detected in 9 of the 13 diets. Eleven of the 13 diets contained GMOs that are grown with large amounts of Roundup.

It should be noted that one of these feeds was used in DuPont’s regulatory study on GM Roundup-tolerant oilseed rape. The type of feed given to the control animals in the DuPont study was found to contain significant amounts of Roundup residues, at levels known to cause toxic effects. The study concluded that the oilseed rape in question was safe, yet it is obviously flawed.

It therefore appears that the long-term consumption of contaminated feed interferes with good experimental practice and that the cause of diseases and disorders found in laboratory rats has been too quickly attributed to the genetic characteristics of the species used. Contrary to the assertions of the health agencies, these diseases cannot be called “spontaneous or natural”. Further, the new study shows that the results of a number of regulatory toxicology tests conducted to date are highly questionable. Does the new study bring us a step closer to understanding the compromises and laxity of the methods of some experts?

In this way, countless industrial products that are potentially dangerous for public health have been helped onto the market.

Laboratory rodent diets contain toxic levels of environmental contaminants: Implications for regulatory tests.

Authors: Robin Mesnage and Nicolas Defarge*, Louis-Marie Rocque, Joel Spiroux de Vendômois, and Gilles-Eric Séralini.

* These authors contributed equally to this work and should both be considered as first authors

Dr. Jim Yong Kim, President of the World Bank, emphasizes the importance of measuring and detecting co-morbidity variables in the 2010 Lancet Burden of Disease Report. Co-morbidity variables for humans include examples such as neurological illness and H1N1 pediatric fatalities; or lung disease and H1N1 fatalities.

Discriminating precisely how much lab rats eat toxic diets, especially when they are supposed to be controls, is necessary for progress in modern medicine, using superstring bio-physics, to cure disease like H1N1. Superstring physics equations in any nth dimension can provide solutions for medicine and agriculture in our 4-dimensional world. However, this depends on precise measurements and data collection. Precise measurements and collection of accurate data concerning the rats’ feed, can even lead to more successful solutions where the current biotech corporate paradigm has failed. Thus the new study in PLOS ONE is of vital importance to helping cure international disease problems. This includes discriminating any co-variables that may be coming from biotech side effects in Korean MERS virus fatalities.