With the publication of the Monsanto Papers in August 2017, new light was shed on the much-publicised retraction of a 2012 study by a primarily French team led by Prof Gilles-Eric Séralini.

Source: https://gmwatch.org

The study had found serious harm to the health of laboratory rats from consumption of two of Monsanto’s products, the GM maize NK603 and the herbicide Roundup, which the maize is engineered to tolerate, fed at environmentally relevant doses. The new paper reviews the history of the retraction and describes how it was engineered by Monsanto with the apparent collusion of the the editor-in-chief of the journal.

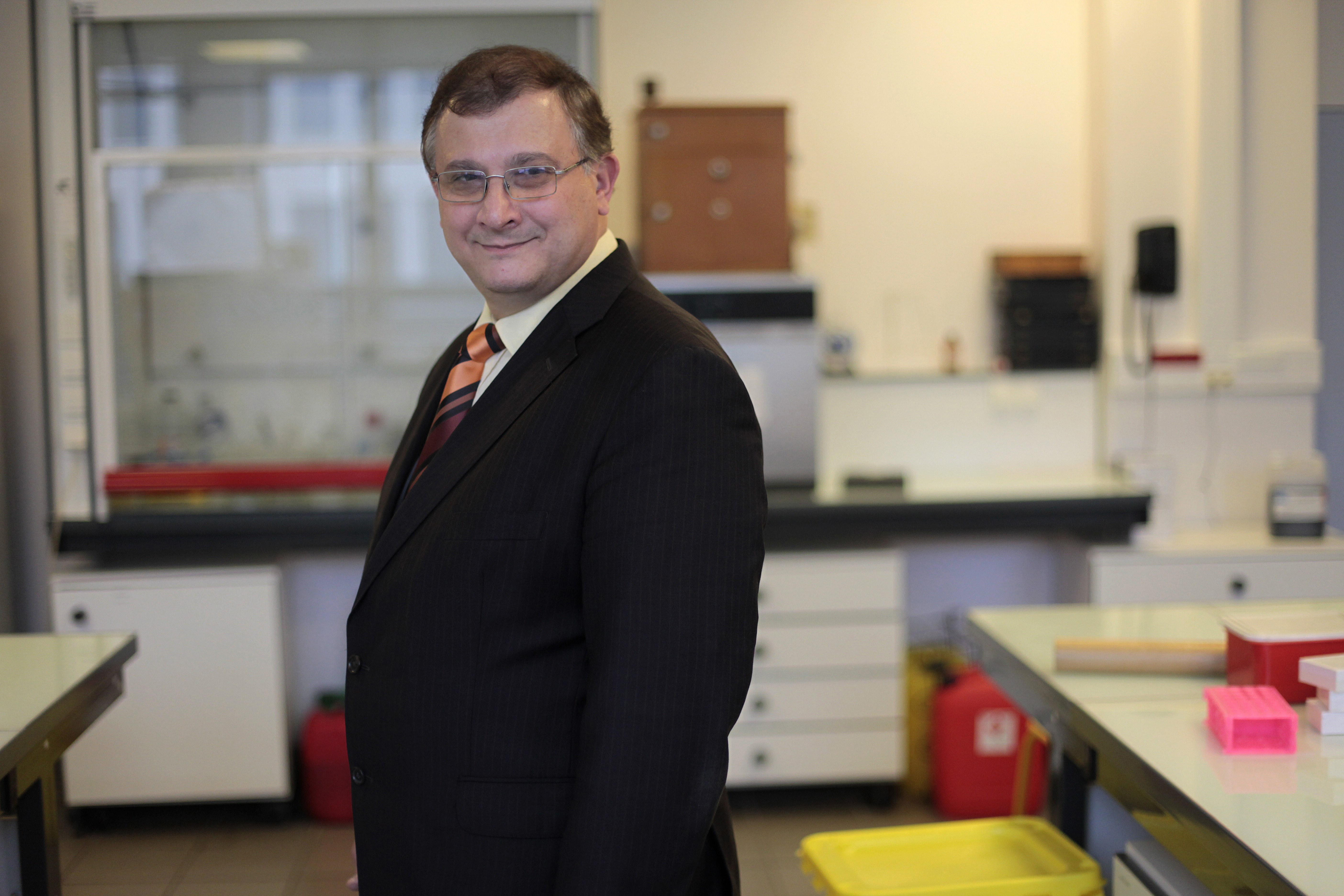

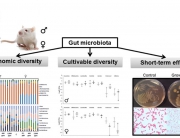

A newly published paper by Dr Eva Novotny, “Retraction by corruption: the 2012 Séralini paper”, describes the rat feeding trial by the Séralini team and the previously published trial by Monsanto scientists. The latter had concluded that the GM maize is “safe and nutritious”, but did not investigate the effects of Roundup and was too short to examine long-term effects – only 90 days compared with the two-year period of the Seralini study.

Because the results of the Séralini study brought into question the safety of all GM crops (because they are not tested in long-term feeding studies), and also the safety of Monsanto’s widely-used herbicide Roundup, Monsanto’s future and the future of GM crops in general were suddenly in jeopardy. Publication of the Séralini paper therefore caused a hailstormof criticism which ignored the possibility that these products were harming the health of people or animals that consumed the maize or traces of the herbicide on food crops.

The new paper begins with a description of the earlier paper by Monsanto scientists, highlighting what Dr Novotny sees as the shortcomings of the design and comparing it with the Séralini paper. She states that despite several relative strengths of Séralini’s study, critics denounced it severely, claiming that he used the ‘wrong’ strain of rat and not enough rats per group (only 10) – even though these aspects were essentially the same as in the Monsanto study. Although Monsanto had 20 rats per group, only 10 animals from each group were used in the analysis of blood and urine; and no explanation was given of the method of selection. This left open the possibility that the healthiest rats were selected from groups fed the GM maize and the unhealthiest were chosen from the control group – thus minimizing any differences between the treatment and control groups.

At issue here is the length of time that the two studies lasted. For a long-term two-year study such as Séralini’s, some scientists argue that more rats are needed than in a 90-day subchronic study such as Monsanto’s. The aim in using more rats is so that the age-related diseases that naturally occur in older rats do not get confused with the effects of the substance under test. Nevertheless, standard OECD long-term toxicity protocols, while they recommend using 20 rats per sex per group, only require 10 per sex per group to be analysed for blood and urine chemistry – the same number as Séralini used and analysed. Thus the Séralini study is comparable to these OECD protocols with regard to numbers of rats analysed.

Dr Novotny states that criticisms of the Séralini study were largely based on the incorrect assumption that it was a carcinogenicity study, although the paper was entitled “Long term toxicity of a Roundup herbicide and a Roundup-tolerant genetically modified maize”. In addition, the authors stated in their introduction that they had no reason or intention to carry out a carcinogenicity study. The significance of the distinction between a carcinogenicity study and a toxicity study is that investigation of carcinogenicity requires at least 50 rats per group, to avoid a ‘false negative’, i.e. failing to spot instances of a rare occurrence. But the statistician Paul Deheuvels countered that the very fact that increases in tumours were seen in the Séralini experiment in groups of only 10 animals makes it probable that the effect is real.

Whichever side of the argument one falls on regarding numbers of rats, the necessity to report tumours in toxicity studies is not in doubt. Standards set by the OECD for toxicity studies require the development of tumours to be reported. In this respect, it would have been remiss of Séralini’s team to have kept quiet about the tumours.

The Monsanto study showed statistically significant differences between the GM-fed rats and the controls, but Dr Novotny explains that these were dismissed as being “not biologically meaningful” — a scientifically invalid assumption because no evidence was presented to back it up. The death of one rat was also confidently dismissed as not being related to the diet, even though the cause of death could not be ascertained.

In comparing Monsanto’s study with Séralini’s, Dr Novotny argues that Monsanto’s study design falls short. For example, the base diet used by Monsanto, including that of the control rats, was almost certain to have included a large proportion of other GMOs. Seralini’s team, on the other hand, grew their feed especially and tested their base diet for GMOs – finding none.

Yet despite these factors, all criticism fell upon Séralini’s study, which found harm from the GM maize and Roundup, and no criticism was raised against Monsanto’s study, which declared the GM maize to be safe and nutritious.

Among those who dismissed Séralini’s results were the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). However, some EFSA experts have ties to the the GM industry and the agency was essentially defending its own previous opinion that the GMO tested was safe.

Dr Novotny recounts that one important critic, who consulted with Monsanto as to what to say by way of denunciation, was Prof Richard Goodman, who was then made associate editor for biotechnology by the editor-in-chief of the journal that had published both the Monsanto and Séralini papers. Unusually, a second peer review of the Séralini study was undertaken, with (again unusually) the evidence of the raw data. Nothing amiss could be discovered; but, 14 months after the Seralini paper first appeared online in the journal, the editor-in-chief, A. Wallace Hayes, retracted the paper on the sole grounds of its being “inconclusive”. This is a unique and unrecognised reason for the retraction of a scientific paper. Dr Novotny counters that most scientific papers must be considered inconclusive. The retraction led to another round of reprisals, this time from independent scientists who pointed out the unfair treatment of papers finding harm from GM products in comparison with those finding safety. Eventually the paper was republished by another journal.Replica watches

Later research

Since the republication of the Séralini study, subsequent developments include a research finding that most of the standard rodent diets tested that are used as the basis for the feed given to rats in laboratory trials are contaminated with pesticides and unlabelled GMOs. This contamination casts doubt on the reliability of all previous studies that used these diets yet failed to control for these elements. Other studies support aspects of Seralini’s work, including a molecular analysis of the body tissues of the rats fed the lowest dose of Roundup, which showed that they suffered from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Monsanto orchestrated retraction

Dr Novotny recounts that the manner in which the retraction of the Séralini paper was brought about became clear when Monsanto’s internal emails, memos and other documents were released for publication by the judge in a legal case charging Monsanto with causing non-Hodgkin lymphoma in people using Roundup. The disclosure was made after Monsanto failed to take the necessary measures to protect this material. Emails reveal how Monsanto was careful to remain undercover while urging pro-GM scientists to write to the journal to denounce the Séralini study. The journal’s editor-in-chief, who held a paid consultancy agreement with Monsanto, appears to have actively colluded with Monsanto and even encouraged Monsanto to recruit scientists to write critical letters to the journal about the study. He must have known they would fiercely attack any research casting doubt on the safety of their lucrative products. Who the actual peer reviewers were has not been revealed.

Dr Novotny’s account of the events surrounding the Séralini study reveals the depths of deception and malpractice to which some scientists and corporations will resort in order to protect their products, even when they know or suspect that those products are harming the public. The journal that retracted the study, Food and Chemical Toxicology, no longer has Goodman and Hayes in place on its editorial board, but its publisher Elsevier should publish an apology to the Seralini team for its journal’s role in the affair and the resulting damage to the reputations of the scientists involved.

The new paper

Novotny E (2018). Retraction by corruption: the 2012 Séralini paper. Journal of Biological Physics and Chemistry 18 (2018) 32–56.

The abstract is available by clicking on the article in the March 2018 issue, on the journal’s website: http://www.amsi.ge/jbpc

The full paper can be accessed online at http://www.seralini.fr under “Research Papers on GMOs”.

The direct link is http://www.seralini.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Novotny-JBPC-2018-On-Seralini-FCT-retraction.pdf