A scientific study suggesting genetically modified food killed rats has been suppressed because of lobbying by multinational biotech corporations, environmental campaigners claim.

Source: By Rob Edwards heraldscotland.com

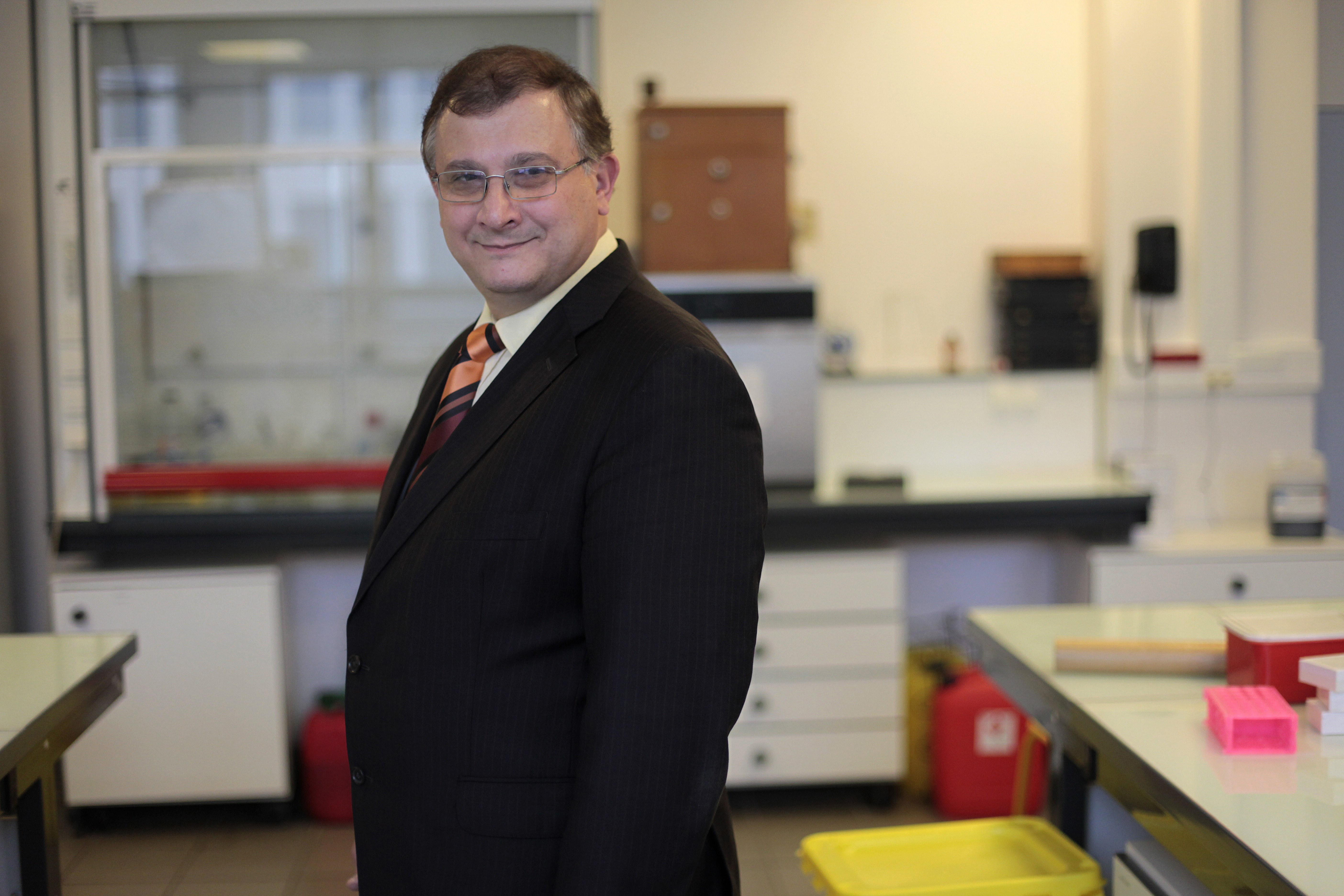

The study by researchers under Professor Gilles-Eric Seralini at the University of Caen in northern France ran into an immediate barrage of condemnation when it was published. As a result, it has been largely ignored by the media, and is mostly unknown in the UK.

But campaign groups are now seeking to change that in a series of public meetings across the UK starring Seralini. He is a molecular biologist and president of the scientific board of the Committee of Independent Research and Information on Genetic Engineering.

The first event in what has been dubbed “GM (genetically modified) Health Risk Week”, is to take place at Edinburgh University tomorrow. On Tuesday, Seralini is giving a briefing in the Scottish Parliament.

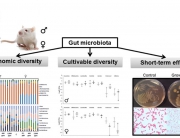

Seralini’s study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Food and Chemical Toxicology last September. It claimed the results of feeding laboratory rats on GM maize produced by US company Monsanto.

He claimed that over two years the rats suffered increased rates of organ damage, tumours and premature death. Researchers blamed GM foods, concluding they “must be evaluated very carefully by long-term studies to measure their potential toxic effects”.

But as soon as it appeared, the study was called “absurd”, “inadequate” and “well below standard”.

Julian Little, chair of the Agricultural Biotechnology Council representing Monsanto and other GM firms, said the study was “deeply flawed in many ways”. The accusation it had been suppressed was “totally crazy”, he added.

“It’s a conspiracy theory that doesn’t stack up”, he said. “More than three trillion meals with GM ingredients have been eaten by people around the world without any substantiated health issues. The question of whether GM is safe is a dead duck.”

Quotes from scientists were gathered and distributed by the Science Media Centre in London, which has received funding from GM firms such as Monsanto, as well as many other sources. A campaign was mounted to persuade the journal to withdraw the study. This was resisted, though the journal has published criticisms by scientists, and responses by Seralini.

The Seralini study “threatened the very basis of the multi-billion dollar GM industry”, according to Claire Robinson, from environmental group GM Watch. She claimed coverage “was stamped out by the pro-GM Science Media Centre.”

She said: “Attacks on Seralini’s study methodology are especially suspect because he simply replicated Monsanto’s own study on the same GM maize but extended it in length. Are we expected to believe this study design is good enough to prove the safety of this GM maize but not good enough to show hazards?”

Robinson, who runs a website dedicated to defending Seralini’s work, accepted no study is perfect. “But Seralini’s is the longest and most thorough to date on a GM food and its associated pesticide,” she added. “We ignore its findings at our peril.”

The Food Standards Agency Scotland has advised that Seralini’s data did not support his conclusions.

But Scottish Environment Minister Richard Lochhead reiterated his opposition to GM crops. He said. “No GM crops are grown in Scotland and we are committed to ensuring that remains the case.”

A new food group, Nourish Scotland, is conducting a public inquiry to find a blueprint for feeding Scotland’s five million people sustainably. Its vision does not include GM food.

Director Pete Ritchie said: “If there is a one in 1000 chance that Professor Seralini is on to something, we should be replicating and building on his studies as a matter of urgency – even a small risk of harming the health of billions of people should be explored openly.”